Who Owns Vande Mataram? Parliament, the Past, and the Politics of a Song

This article explains the complete history of Vande Mataram from its origin in Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Anandamath to the 1930s Congress-Muslim League debate, Tagore and Gandhi’s stance, the two-stanza compromise, and the song’s political use in modern India. It clarifies why the national song still triggers disputes over identity, nationalism, and constitutional values.

The fight over Vande Mataram in today’s Lok Sabha is, on the face of it, about a song. Scratch the surface and you realise it is about ownership of the past: who gets to narrate the freedom struggle, and what kind of India that story is meant to justify now.

On 8 December 2025, the Lok Sabha more or less cleared its calendar to hold a special discussion on the 150th anniversary of Vande Mataram. The government framed it as a solemn tribute: Prime Minister Narendra Modi opened the debate by celebrating the song as the soul and soundtrack of the freedom struggle, the chant that, as the cliché goes, “made British rulers tremble”. But within minutes the commemoration turned into a prosecution. Modi accused Jawaharlal Nehru and the Congress of “dividing” or “breaking” the song in the 1930s to appease the Muslim League, arguing that this act of cutting out the goddess-heavy stanzas was of a piece with the politics that eventually accepted Partition.

In other words, the government didn’t just say, “this song is important”. It said, “look at what your side did to this song, and therefore to the nation.” That’s quite a lot of weight for a lyric to carry.

The opposition wasn’t exactly in a mood for group singing either. Congress leaders, in Parliament and outside, responded that the party had not “betrayed” Vande Mataram but tried to keep it usable for a country that was not, as they insist on reminding everyone, exclusively Hindu. Jairam Ramesh, for instance, pointed to historians like Sugata Bose and to Rabindranath Tagore’s own advice in 1937: keep the first two stanzas that speak of the land in poetic but relatively ecumenical terms, drop the later ones that identify the Mother explicitly with Durga and Lakshmi, and avoid forcing Muslims to join a song that sounds, to them, like polytheistic worship. Priyanka Gandhi used her Lok Sabha speech to accuse the prime minister of “selective history”, argue that the controversy itself is being pushed because West Bengal is heading into elections, and to defend Nehru as someone who had spent as many years in prison as Modi has now spent in office.

Outside Delhi’s bubble, the row has escaped into state politics like dye seeping through cotton. Uttar Pradesh chief minister Yogi Adityanath has announced that singing Vande Mataram will be made compulsory in all educational institutions, presenting it as an expression of patriotism and warning in his usual mad monk mode that “new Jinnahs” emerge when society is divided and the national song disrespected. In Hyderabad, a municipal meeting turned into a shouting match when BJP corporators demanded that everyone stand and sing the song to mark its 150 years and some of them declared that those who refuse are “not eligible to live in India”. A Maharashtra minister recently said, bluntly, that people who are “ashamed” to chant Vande Mataram should leave the country.

So, Parliament is the main stage, but there are smaller, noisier theatres all over the place where the same script is being tried out: this song equals the nation; hesitation around it equals disloyalty.

The irony is that none of this is new. Every argument being shouted today has an ancestor crouching somewhere in the early 20th century. The current debate doesn’t merely “hark back” to the independence struggle; it actively treats those earlier quarrels as a kind of user manual.

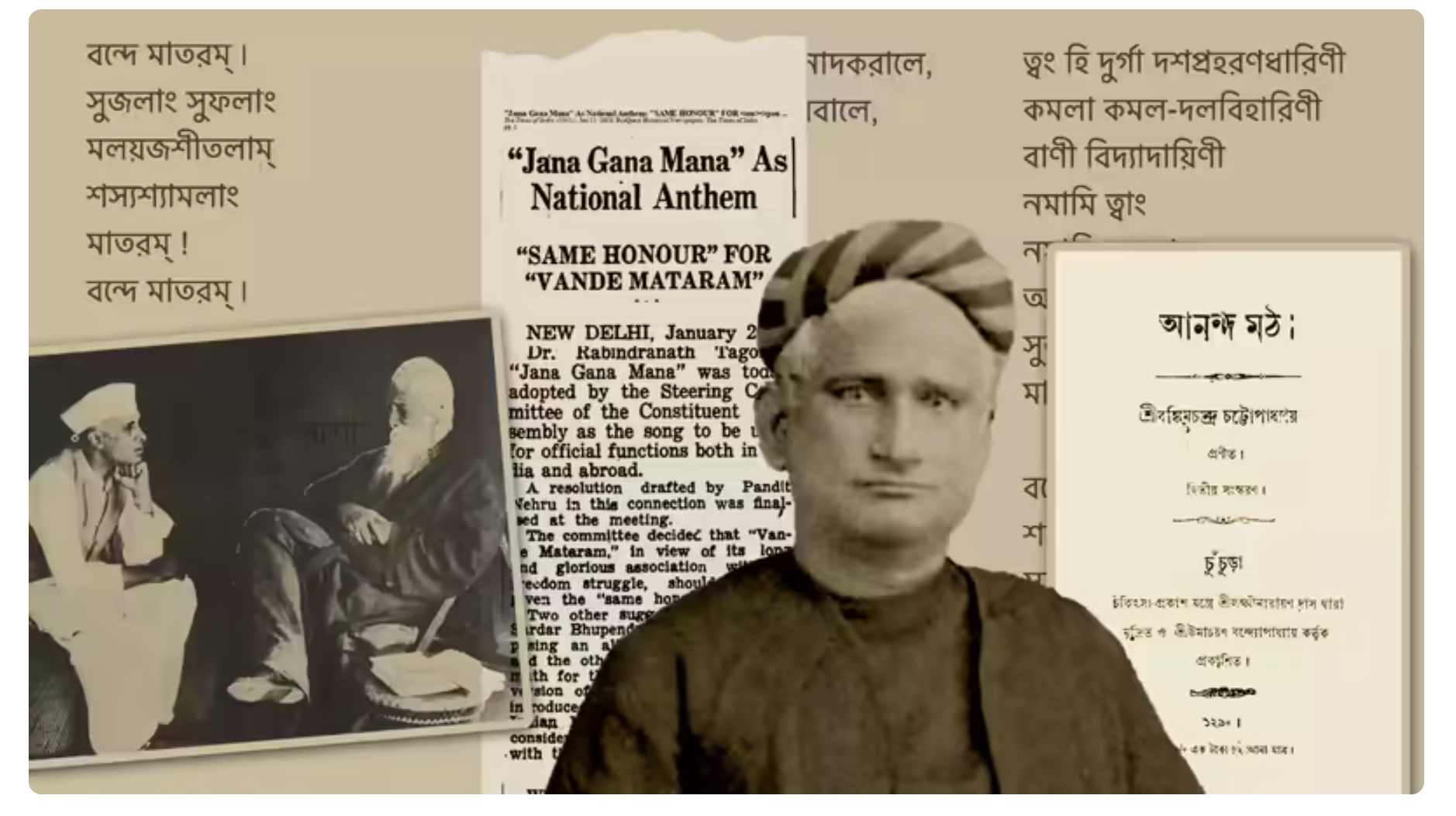

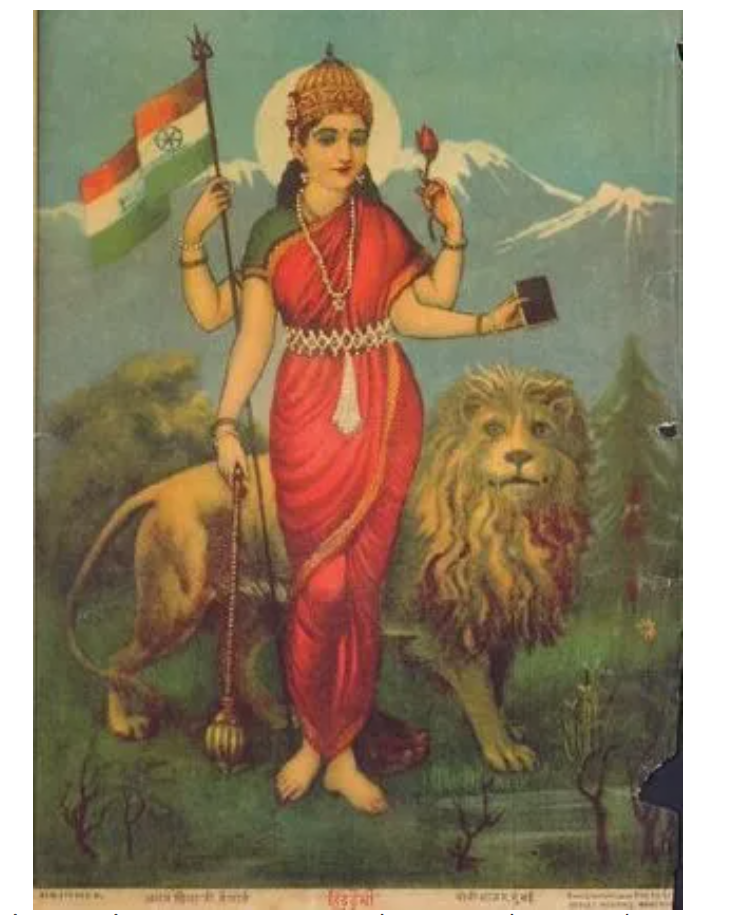

Start with the text itself. Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay wrote Vande Mataram in the 1870s and later set it inside his novel Anandamath (1882), a feverish story about bands of Hindu ascetics waging holy war against a corrupt Muslim nawab in famine-stricken Bengal. In that fictional world, the Mother is not a cute cartographic silhouette draped in a tricolor sari; she is a newly minted goddess who fuses the land, Hindu civilization and martial fury. Tanika Sarkar’s famous essay “Birth of a Goddess” shows in painful detail how this goddess is born in the novel out of violence and loss and is defined explicitly against Muslim rule. When later stanzas call the Mother Durga and equip her with ten hands and weapons, that is not harmless allegory; it is a program. The hymn, in the novel, is a battle song in a Hindu–Muslim war.

Yet the song slipped its original home and acquired a second life. By the 1890s it was being sung at Congress sessions; Tagore performed it at the 1896 Calcutta session, and Aurobindo translated parts of it into English. It became the signature tune of the Swadeshi movement after the 1905 partition of Bengal, shouted in processions, printed on pamphlets, used as a sonic banner of defiance. To thousands of people who sang it in that period, Vande Mataram meant “down with colonial rule”, full stop.

But of course there was no full stop. Muslims increasingly pointed out that in its longer form, and in its novelistic context, the nation being deified looked suspiciously like a Hindu goddess, and the enemy being vanquished looked suspiciously like them. Mohammad Ali Jinnah and the Muslim League argued in the 1930s that insisting on the song at mixed gatherings effectively turned legislative proceedings into Hindu religious rituals.

This is where the story takes the turn that today’s politics is obsessed with. In 1937, the Congress Working Committee, led by Nehru, was forced to deal with the controversy. They consulted Tagore. Tagore, according to later accounts and surviving correspondence, said something quite subtle: he loved the “tender and devotional” spirit of the opening but was wary of the goddess-worship and militant imagery in the rest. He essentially proposed that the national movement adopt the first two stanzas as a separate, “universal” song and quietly drop the rest for official purposes.

The CWC resolution that followed did exactly that. It acknowledged that Vande Mataram had become “a national song for many years” but said that “objections raised by our Muslim friends” were “valid” as far as the later verses were concerned. It recommended that only the first two stanzas be sung at officially organised gatherings and reminded organisers that they were free to choose other patriotic songs altogether. Gandhi, in his own writings and speeches, took a similar line: he called the song a great rallying cry of the struggle, but insisted that it should never be thrust on those who objected, and even compared the emotional force of the chant to “Allahu Akbar” to make clear that no single religious idiom had a monopoly on patriotism. Nehru, writing later to Subhas Bose, described much of the controversy as manufactured by “communalists” and said that while he personally found the whole song harmless, he understood why its background might irritate Muslims.

When the Constituent Assembly finally settled the question of national symbols, it carried this messy compromise into the new republic: Jana Gana Mana was adopted as the anthem; the first two stanzas of Vande Mataram were recognized as the national song; no one was compelled, in law, to stand up and sing either.

Now, if you freeze the frame there and ask, “What’s the moral of this story?”, you can get at least two very different answers.

One moral, which you could call the secular-democratic reading, is that multi-faith nationalism involves constant editing of one’s favourite symbols. The majority’s beloved song had to be trimmed because it carried, baked into its later verses and novelistic backstory, a theology and a history that marked Muslims as outsiders and enemy rulers. The fact that Tagore, Gandhi and Nehru all endorsed some version of the two-stanza compromise can be read as an early experiment in constitutional behavior: keep what unites, drop what wounds, don’t compel anyone.

Another moral, which is more or less the one being performed in Parliament today by the BJP, goes like this: look how the Congress, from Nehru onwards, kept kneeling before “communal elements”; look how they chopped up a sacred national song to appease the Muslim League; look how that mindset of concession eventually led them to agree to Partition. In this version, the 1937 compromise is not clever pluralist statecraft; it’s the original sin of “appeasement”. It’s a performance of toxic masculinity by the uncle cohort.

Notice the shift. The same archive — Tagore’s caution, Gandhi’s letters, Jinnah’s speeches, the CWC resolution — can be treated as a laboratory of how to live together in difference, or as evidence in a trial of who betrayed whom. History as manual versus history as charge-sheet.

And that is really the heart of the present Bande/Vande Mataram issue. The past is not merely being remembered; it is being mined. Not just for inspiration, but for ready-made scripts.

Take the current moves to mandate the song in schools in Uttar Pradesh. Yogi Adityanath describes the policy as non-religious, about a “sense of respect” and national unity, and explicitly links refusal to sing to dangerous divisive tendencies and the spectre of “new Jinnahs”. The logic is clear: if earlier concessions to minority sentiment supposedly produced Partition, then the lesson is that there must be no such concessions now. The edited, cautious, voluntary version of Vande Mataram that emerged in the 1930s becomes, in this retelling, a cautionary tale of what happens when you care too much about pluralism.

Or look at those city-level flashpoints: corporators told they are “not eligible to live in India” if they resist singing the song; mayors suggesting that those who won’t chant it should leave the country; angry scenes in Hyderabad and elsewhere when some councillors sit while it is played. Here, the song has been quietly re-classified from “one powerful symbol among many” to “the basic citizenship test”. The nuance of the old resolution — sing the first two stanzas if you like, or use another patriotic song, but don’t make it a wedge — has evaporated.

Interestingly, while Hindu nationalist politics leans hard into this loyalty-test framing, Muslim religious leadership today often sounds eerily similar to the more cautious voices from the 1930s. Organizations like the Jamiat Ulama‑i‑Hind have repeatedly said in the current debate that they have no objection to others singing Vande Mataram, and that Muslims, too, love their country; their problem is with the theological content of the poem, where the homeland is likened to a deity and addressed in the language of worship. Constitutionally, they argue, nobody should be forced into that kind of devotional act. Their plea is basically: respect both patriotism and monotheism, and don’t make this into a club to beat us with.

Meanwhile, historians are waving their own flags, but of footnotes rather than party colours. Scholars like Tanika Sarkar and Joyjit Ghosh have spent years showing how Anandamath constructs a Hindu nation through a new militant goddess and how Tagore’s later novel Ghare Baire can be read as an anxious critique of precisely that kind of devotional, masculinist nationalism. Their work suggests that the right lesson to draw is not “make the song compulsory” or “ban it” but “handle with care, and remember that symbols are never innocent”.

Bharat Mata painting by Raja Ravi Varma Press Oleograph 1935 (Image Source: Goddess and the Nation)

But we are not living in an age of careful handling. We are living in an age of historical cosplay.

The current Lok Sabha debate, long and theatrical as it is — nearly ten hours in the lower house alone — unfolds as if the primary task of Parliament is to re-enact the 1930s but with the ending rewritten. Where Nehru once wrote to Bose to calm everyone down about what he called a “manufactured” controversy, today’s leaders keep turning the volume up. Where the CWC once accepted Muslim objections as “valid” for certain verses, the ruling party now treats those objections as proof that Muslims were always unreasonably sensitive and that Congress was terminally weak.

History, in other words, is no longer primarily a source of lessons about how fragile pluralism is. It is a catalogue of grievances and grievances-to-go, each with a detachable script that can be replayed on a new stage.

The Vande Mataram story could have been told as a parable of creative compromise: a community wrestling with a song that is both inspiring and exclusionary, trimming it, translating it, arguing over it, and finally parking it in a slightly awkward but workable constitutional position, side by side with Jana Gana Mana. Instead, a different kind of moral is being squeezed out of it: that the majority’s cultural comfort should never again be rearranged for the sake of minority unease; that those who hesitate before a symbol beloved of “the nation” are suspect; that past conciliation is evidence of present treachery.

Whether one loves the song or finds it impossible to sing, that shift in how we use history is worth worrying about. A democracy that learns from its past will remember how quickly devotional slogans can be weaponised and how hard its founders worked to blunt some of those edges. A democracy that raids its past for slogans, on the other hand, will happily drag its half-resolved quarrels from the 1930s into the present, intact and sharpened. In that sense, the Lok Sabha’s Vande Mataram debate is not really about 150 years of a song. It is about whether we are still willing to edit ourselves for each other. Or harmonize the way we sing to create a shared song.

FAQs

Q1. Why was Vande Mataram controversial in the 1930s?

Because the longer version included goddess imagery drawn from Anandamath, which many Muslim leaders viewed as religious in nature.

Q2. What did Tagore and Gandhi say about Vande Mataram?

Both supported the song’s first two stanzas but advised against forcing anyone to sing the full version.

Q3. What decision did the Congress Working Committee make in 1937?

It recommended using only the first two stanzas at official gatherings to respect diverse religious beliefs.

Q4. Why is Vande Mataram debated in Parliament today?

Parties use the song’s history to frame political narratives around nationalism, minority rights, and “appeasement.”

And now, because you asked for it, a further reading binge:

On the 2025 Parliament debate

“PM addresses the special discussion on 150 years of the National Song Vande Mataram in Lok Sabha” – Press Information Bureau / pmindia.gov.in (Dec 2025). Official summary of Modi’s speech, useful for seeing the government’s own framing of the debate. PM India

“150 years of Vande Mataram: Why BJP and Congress are fighting over its ‘missing stanzas’” – Times of India explainer (Dec 2025). Lays out the immediate Lok Sabha context and the political sparring over the “deleted” verses. The Times of India

“Vande Mataram Lok Sabha Discussion Highlights” – India Today live blog (Dec 2025). Blow‑by‑blow account of the day‑long debate in the Lok Sabha and the follow‑up in the Rajya Sabha. India Today

“Nehru‑led Congress knelt before Jinnah to cut ‘Vande Mataram’: PM Modi in Lok Sabha” – Economic Times (Dec 2025). Captures the key accusatory line from Modi and its link to present electoral politics. The Economic Times

“Priyanka Gandhi’s fiery Lok Sabha speech… rebuffs PM Modi’s critique on Vande Mataram issue” – UNI / uniindia.com (Dec 2025). A good read for the Congress rebuttal and its defence of the party’s historical role. UniIndia

“150 Years of Vande Mataram: Why India’s National Song is Sparking Debate in Parliament – Explained” – OneIndia (Dec 2025). Short explainer that links the 150‑year commemoration to the 1937 controversy. https://www.oneindia.com/

“The Vande Mataram debate and the politics of manufactured controversy” – Counterview (Dec 2025). Strongly argued column that situates the parliamentary debate within a broader pattern of polarising culture‑war politics. Counterview

“Historical interpretations and political disputes: The Vande Mataram controversy” – Devdiscourse (Dec 2025). Summarises how ruling and opposition benches accuse each other of distorting history in the recent Rajya Sabha debate. Devdiscourse

Historical explainers on the song and the 1930s debates

“Vande Mataram: What Gandhi, Tagore, Jinnah said about the song” – Indian Express, Explained (Dec 2025). Excellent overview of Muslim League objections, Tagore’s letters, and Gandhi’s cautious support, including key quotations and archival references. The Indian Express

“How the Muslim League and the Congress viewed Vande Mataram” – Indian Express, Explained (Dec 2025). Focuses on the 1937 CWC resolution and traces how the “two‑stanza” solution was crafted and later taken into the Constituent Assembly. The Indian Express

“Vande Mataram at 150: How the National Song is different from the National Anthem” – Indian Express (Dec 2025). Shorter piece that clarifies the legal‑symbolic status of national song vs anthem. The Indian Express

“Was Vande Mataram broken up to appease Muslims? Here are the facts” – India Today explainer (Dec 2025). Examines the “appeasement” claim using archival material and historians’ views. India Today

“Vande Mataram row explained: What it means, its Anandamath novel link, were some stanzas removed and why it’s political again” – Economic Times (Dec 2025). Very useful one‑stop explainer connecting the novel, the 1937 decision, and the 2025 Parliament debate. The Economic Times

“Vande Mataram: How India found its voice through a 19th‑century poem that became the national song” – Economic Times (Dec 2025). A slightly more narrative piece tracing the song’s journey from Bankim to the present. The Economic Times

“Vande Mataram controversy: What Nehru really wrote to Subhas?” – DNA explainer (Dec 2025). Reproduces and contextualises Nehru’s 1937 letter to Subhas Bose. DNA India

“Vande Mataram row: the 1937 paper trail that unsettles a tidy narrative” – NewsDrum (Nov 2025). Walks through correspondence and resolutions around the song to show how messy the decision‑making really was. NewsDrum

On Muslim perspectives and ongoing objections

“Controversy over India’s National Song ‘Vande Mataram’ – Analysis” – Eurasia Review (Nov 2025). Outlines Muslim theological objections and the anti‑Muslim content of Anandamath while also acknowledging the song’s patriotic role. Eurasia Review

“Vande Mataram debate: Respecting beliefs & constitutional freedoms” – Devdiscourse (Dec 2025). Focuses on Jamiat Ulama‑i‑Hind’s nuanced position: no objection to others singing it, but discomfort with its polytheistic theology and political misuse. Devdiscourse

Scholarly and long‑form work on Anandamath, nationalism and communalism

Tanika Sarkar, “Birth of a Goddess: ‘Vande Mataram’, Anandamath, and Hindu Nationhood” – Economic and Political Weekly 41(37), 2006. Classic article unpacking how the novel and song construct a Hindu nation through the figure of a militant mother goddess. EPW

“Birth of a Goddess: ‘Vande Mataram’, Anandamath, and Hindu Nationhood” – JSTOR version. Online access point for Sarkar’s piece with easier navigation. JSTOR

“The Birth of a Goddess: Bankimchandra Chattopadhyaya’s Anandamath” – in Hindu Nationalism in India (Oxford University Press, 2022). A book chapter expanding Sarkar’s arguments in a broader study of Hindu nationalism. OUP Academic

“From Nation to Post‑Nation: The Making and Unmaking of National Consciousness in Anandamath” – academic paper on Academia.edu. Reads the novel as a text of crisis and fragmentation, not just heroic consolidation. Academia

“‘Vande Mataram!’: Constructions of Gender and Music in Indian Nationalism” – André J. P. Elias. Explores how performances of the song, including at Wagah, encode gendered and militarised ideas of the nation. Scholars@HKBU

“Critiquing Nation as a Goddess: The Home and the World and Anandamath” – Joyjit Ghosh. Puts Bankim and Tagore into dialogue, reading Ghare Baire as a critique of the kind of nationalism embodied in Anandamath and Vande Mataram. Gitanjali and Beyond

“Vande Mataram: Ideological Background of Militant Nationalism…” – V. Venkatraman. Looks at how the song fed revolutionary literature and militant nationalism in the Madras Presidency. ResearchGate

“The Legacy of Vande Mataram on Pre‑Independent Society” – IJRSSH paper. A more straightforward historical overview of the “Vande Mataram movement” and its role in the freedom struggle. IJRSSH

Contemporary opinion across the spectrum

“Gandhi’s vision of the song Vande Mataram is inclusive, not divisive like now” – The Wire. Argues for returning to Gandhi’s non‑compulsory, non‑sectarian reading of the song. The Wire+1

“Vande Mataram: Keep Politics Out Of It” – Free Press Journal (Dec 2025). Pleads for de‑politicising the song while acknowledging both its inspirational role and the reasons for minority unease. Free Press Journal

“Controversy over India’s National Song Vande Mataram – Analysis” – P. K. Balachandran (Eurasia Review, Nov 2025). A readable survey of the historical controversy, sympathetic to both patriotic attachment and minority anxiety. Eurasia Review

“Inside Anandamath: The celebrated book that gave India ‘Vande Mataram’” – NDTV (Nov 2025). Introduces the novel for a general audience, with nods to its communal themes and present‑day appropriations. www.ndtv.com