“Where Do We Go From Here?”: Sunita Viswanath Reads at MLK Day Vigil for Courage and Conscience

On Monday, January 19, 2026, the Cathedral of St. John the Divine invited New York City into a Martin Luther King Jr. Day vigil titled “Where Do We Go From Here? A Vigil for Courage and Conscience.” With communal song, prayer, candlelight, and preaching by the Rev. Canon Dr. Kelly Brown Douglas, the service was framed not as commemoration-as-comfort, but as a gathering for moral attention—an invitation to listen deeply and leave strengthened for the work ahead.

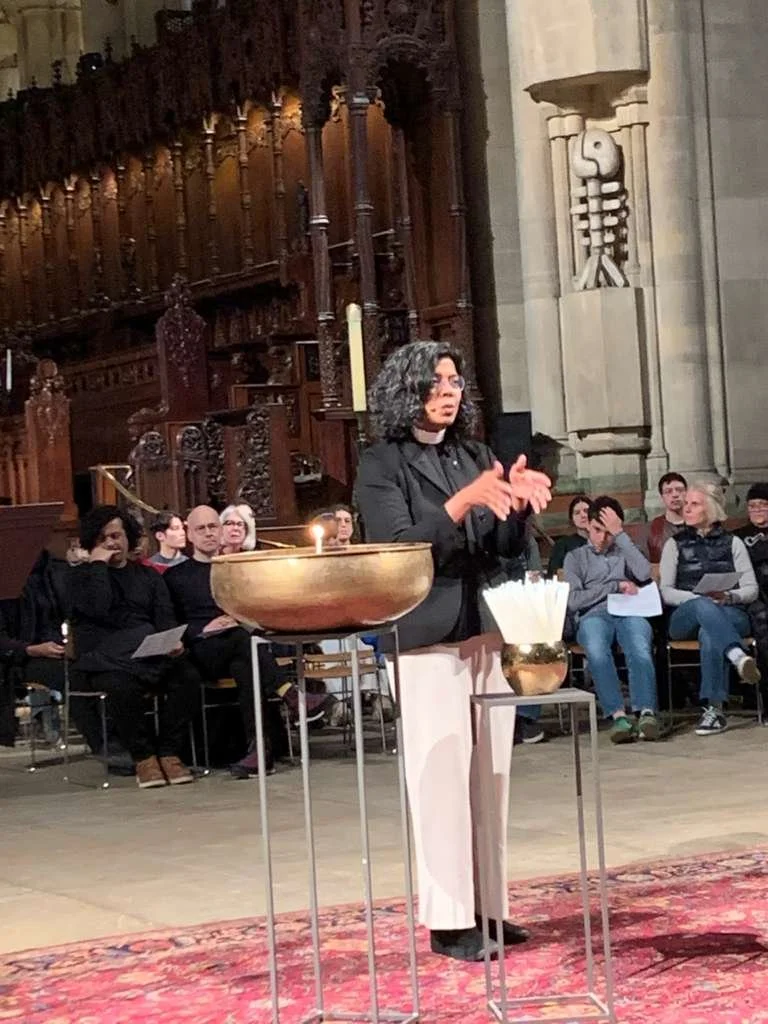

Sunita Viswanath, Executive Director of HfHR, served as a reader during the vigil. The readings she offered did not flatten Dr. King into a single, safely packaged symbol. Instead, they traced the sharper edges of his public witness: his insistence that justice cannot be postponed for the sake of social ease; his refusal to confuse nonviolence with passivity; and his understanding that dignity is indivisible—across race, caste, borders, and wars.

Sunita opened with an invocation that braided King’s Beloved Community to the spiritual and political demands of this moment. She named a world in which authoritarianism “at home and abroad” works by dividing people, shrinking empathy, and training us to accept cruelty as normal. In that landscape, she suggested, we do not need vague appeals to calm. We need moral heat and moral motion: “prayers NOT of peace,” she read, “but of righteous rage and resistance”—and then, crucially, the next step: not only to rage and resist, but to take collective action “with the urgency of now,” refusing the temptation to leave anyone behind

From there, the reading moved into one of King’s most enduring confrontations: the warning, in Letter from Birmingham Jail, about the seductive danger of moderation. King’s critique is often misremembered as anger for anger’s sake. In truth, it is an ethical diagnosis—of the social preference for quiet over justice, and the endless demand that the oppressed make their freedom “reasonable.” Sunita read King’s confession that he had become “gravely disappointed with the white moderate,” a line that still stings because it is not about personal prejudice so much as political inconvenience: the moderate who agrees in principle but cannot tolerate urgency in practice

Cathedral of St. John the Divine

But King’s moral imagination, as Sunita’s selection made clear, is not accusatory—it is instructive. The vigil’s theme is courage and conscience, and King offers both as disciplines. Sunita read his insistence that the movement must not drift into either of two failures: “the ‘do nothingism’ of the complacent” or “the hatred and despair” that violence breeds. Between them, King argues, is “the more excellent way of love and nonviolent protest.” Hearing these words in a sanctuary filled with song and prayer, it was hard to mistake them for sentimentality. King’s “love” is not softness; it is a practice of resistance that refuses to surrender its humanity, even while confronting forces determined to strip humanity away.

One of the most powerful passages Sunita offered came from King’s sermon sometimes referred to as “I am an untouchable.” King recounts traveling in India and being introduced to students—the children of people formerly labeled “untouchable”—as “a fellow untouchable from the United States of America.” He admits he was “shocked and peeved,” and then describes what the phrase opened up: a recognition that in an “affluent society,” millions were still trapped in poverty and neglect, still pushed into “rat-infested” housing and inadequate schools. “Yes,” King concludes, “I am an untouchable… and every Negro… is an untouchable.” In a single pivot, he links struggles without collapsing their specificity—making clear that systems of dehumanization may take different names, but they rhyme in structure and effect.

Dr. Sarah Sayeed Reads at MLK Day Vigil for Courage and Conscience

This portion of the reading carries particular resonance. It reminds us that caste is not an “over there” problem that belongs to another time or another place. It is a logic of social hierarchy—of whose suffering is tolerated, whose voice is discounted, whose life is treated as expendable—that can replicate wherever communities refuse to confront it. King’s words in India do not simply “reference” caste; they help name what solidarity demands: the willingness to see how indignity travels, how it is rationalized, and how it must be opposed without qualification.

Sunita’s reading then widened outward again, toward King’s anti-war witness. From “Beyond Vietnam—A Time to Break Silence,” King insists that “this madness must cease,” speaking as “a citizen of the world” and calling on U.S. leaders to take responsibility not only for pain at home but for devastation abroad. He warns that if the war continued, the world would have “no other alternative” than to conclude the U.S. had “no honorable intentions,” and he presses the necessity of a sharp turn—an act of moral maturity, not mere strategy. This was not included as a sidebar to King’s “real” legacy; it was the legacy, spoken plainly: justice that stops at the border is not justice.

That throughline appeared again in a line Sunita read from a 1967 anti-war rally: “I’m not only going to be concerned about justice for Negroes in the United States… I’m concerned about justice for everybody the world over.” It’s the kind of sentence that sounds obvious until you realize how much political life depends on pretending the opposite—that some people’s suffering is “complicated,” or “unrelated,” or simply not our responsibility.

Finally, Sunita included a set of remarks King offered just one week after the Six-Day War, in a 1967 appearance on ABC’s Issues and Answers. The excerpt does not work as a slogan—and that is part of its point. King holds two moral claims at once: the insistence on Israel’s “right to exist,” and the warning that “for the ultimate peace and security” it would likely be necessary “for Israel to give up this conquered territory,” because holding it would “exacerbate the tensions and deepen the bitterness.” Read in 2026, this section functioned less as a historical curiosity than as a reminder that ethical seriousness rarely fits into the easy binaries that power demands.

The vigil ended the way it began: not with neat resolution, but with a shared sense of charge—song, candlelight, blessing, and sending out Vigil-MLK-2026-1768835855. In a time when MLK Day is routinely softened into ceremony, this service asked something harder: that we stop using Dr. King as reassurance, and return to him as challenge. Sunita’s reading made that challenge audible—rooted in faith, sharpened by conscience, and oriented toward collective action.