UUJME Delegation Update: Witnessing Fear, Hidden Histories, and Moral Responsibility in Palestine

A young Israeli soldier strides up and down our delegation bus, cradling in both hands an automatic rifle, with his fingers curled around the trigger. We are required to show our passports at this Israeli military checkpoint, not for the first time. The intentional intimidation is unmistakable – this is not a casual or friendly interaction. Being a brown-skinned person, I get nervous during ordinary traffic stops in the U.S., so you can imagine the anxiety of a situation like this. As our bus rolls away, having cleared the checkpoint, tears stream down my face knowing that the intimidation and fear tactics that our Palestinian siblings face is far, far worse than anything I will ever experience as a U.S. passport holder. For a brief time, the momentary stress and my sadness at these circumstances overwhelms me.

Though in Palestine, my heart is also thousands of miles from here with siblings in Minnesota. Similar tactics of fear and intimidation are being employed there right now, for seemingly no other reason than to cow people into political submission. Our Palestinian contacts have remarked this week, multiple times, that everything the U.S. experiences is first field tested in Palestine – militarized border security, surveillance of the civilian population, the employment of fear and intimidation, the creation of an environment so hostile that those who can flee will flee and go elsewhere. These connections – both direct and indirect – between Palestine and the U.S. are disturbing.

I am also unsettled by the emerging recognition of how little I have actually known about the day-to-day realities of Palestine. As an undergraduate, I academically specialized in the Arab world. I spent years studying Islam, Arab history, politics, and economics, and the Arabic language. I have served our nation as a U.S. diplomat in the Persian Gulf, helping implement U.S. Middle East foreign policy. I am not an average U.S. citizen when it comes to the Middle East – I have specialized academic training and professional experience in this region.

Despite that, I have been humbled to discover significant gaps in my knowledge regarding Palestine. I only knew a fraction of what we have been learning in-country during this delegation. This has led me to wonder how it can be that someone with specialized training and experience, like myself, has in reality known so little about Palestine. And if I – someone who has a modicum of ‘expertise’ in the region – have had huge gaps in knowledge, what might that mean for the average American, who spends far less time learning about this part of the world?

A few years ago, I created and led a year-long Civil Rights seminar. I chose to offer this seminar for some very specific reasons. As I spent time independently learning about Black history it became clear to me that very little Black history is taught in our nation. One has to actively seek out and learn this history, and even then it might not be easy. This is the phenomenon of hidden histories – histories that for political and cultural reasons are marginalized and/or invisibilized. There are many reasons why certain histories and experiences become invisible: they don’t support the dominant cultural narrative; they evoke feelings of shame; the facts and stories are politically inconvenient or unpalatable, etc. For these and other reasons, histories get suppressed or hidden, and one has to do a lot of excavation work to uncover them. That difficult work of excavation can be historical, cultural, and/or intra-personal – we may have to also excavate assumptions or acculturated norms and understandings. University of Virginia Professor Mar Hicks notes that when important facts and experiences are hidden, “it can lead us to erroneous conclusions about why larger historical events unfolded the way they did.”

Palestine has been a reminder to me that oppression moves in familiar patterns across very different contexts. The experiences of the oppressed are invalidated, denigrated, or hidden. The oppressors justify their actions via narratives of superiority and/or exceptionalism. That sense of superiority is then passed down culturally from one generation to the next. Bellicosity, threats, and violence are used to shut down any critical examination of the oppressive situation. There is often an extraction of resources - labor, money, property – from the oppressed to the oppressor. Most critically, the oppressed are dehumanized, and through that dehumanization are understood to deserve whatever abuse they are suffering.

The challenge in all this is that patterns of oppression can remain alive and undetected if we’re not looking at the full picture – if we’re excluding from our analysis histories and experiences that have been hidden from us.

Making that which has been invisible visible, and then factoring that additional information into our lives, takes effort. It requires getting beyond the hubris of thinking that we already know everything that we need to know about Israel and Palestine. (Unless we’re Palestinian, we probably don’t.) It requires getting beyond the checked-out posture of viewing Israel and Palestine as an intractable problem with no solution. (Checking out allows harm to continue unabated.) It requires confronting the reality that the United States is Israel’s largest funder; if the government of Israel is causing harm, U.S. taxpayers are funding that harm.

We have a moral obligation to learn more, to discuss more, and to effect change where we can. As my delegation experience comes to a close, I, for one, am resolved to do that. I invite you to join me in that commitment.

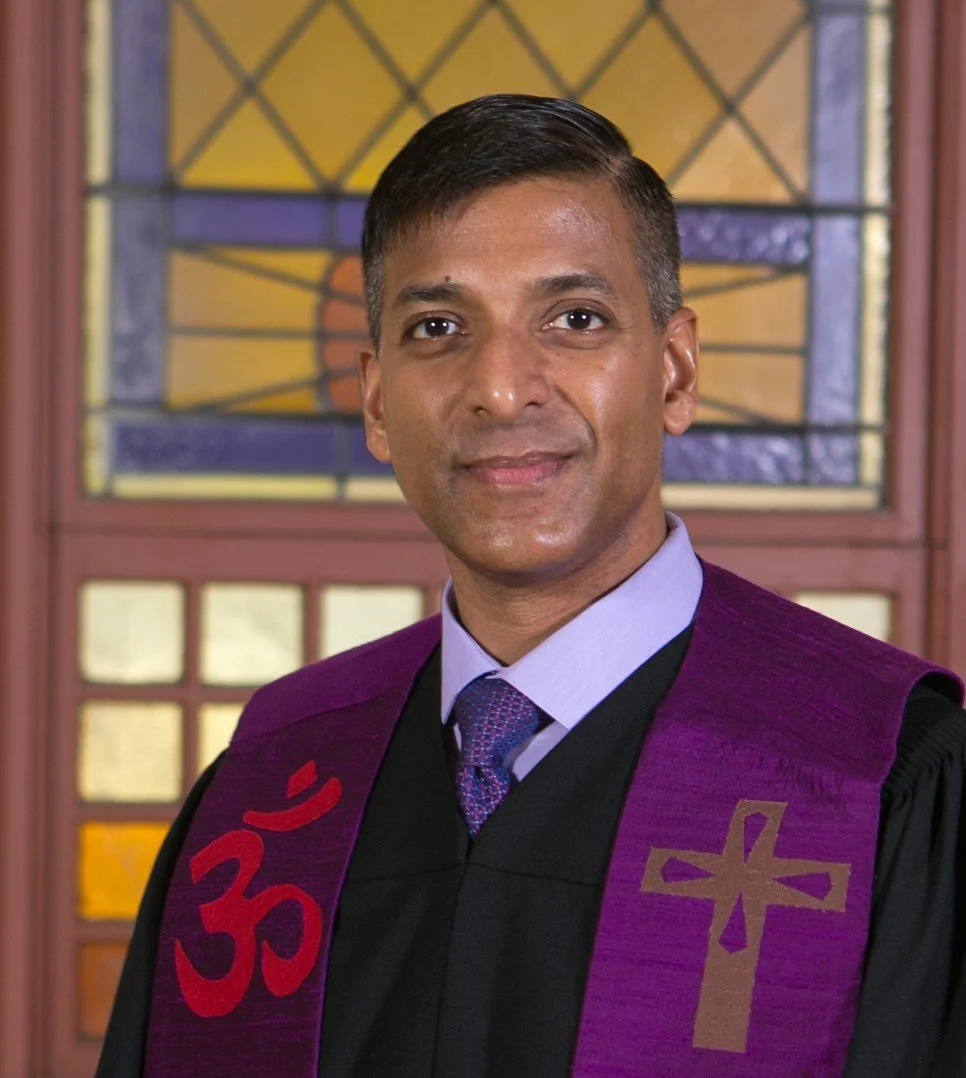

From Palestine with love, Rev. Manish

Rev. Manish Mishra-Marzetti (he/him) serves as senior minister of the First Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Ann Arbor, Michigan. He is the co-editor of Seeds of a New Way: Nurturing Authentic & Diverse Religious Leadership (2024), Conversations with the Sacred: A Collection of Prayers (2020), and the 2018-2019 UUA common read, Justice on Earth: People of Faith Working at the Intersections of Race, Class, and the Environment. He has served extensively in Unitarian Universalist leadership, including as co-chair of the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee (UUSC) Board of Trustees, a member of the UUA Board of Trustees, president of the Diverse and Revolutionary Unitarian Universalist Multicultural Ministries (DRUUMM), commissioner on the UUA Commission on Appraisal, secretary of the board of Starr King School for the Ministry, and as an author and advocate of the 2007 General Assembly resolution confronting gender identity-related discrimination. He brings to the ministry his multicultural experience serving as a U.S. diplomat during the Clinton administration.