MLK Day 2026: When Remembrance Becomes a Battleground

Martin Luther King Jr. is often treated like a national heirloom: polished, safely displayed, and spoken of in the past tense. But MLK Day (January 19, 2026) arrives this year with a sharper edge—because the meaning of the day is being contested in real time.

You can’t “cancel” MLK Day by decree. But you can hollow it out: reduce it to a handful of soothing quotes, strip public institutions of the capacity to teach the full story, and recode civil-rights memory as something “divisive” or “extra.” One small but telling example: the Department of the Interior’s 2026 list of National Park “fee-free days” includes Flag Day/President Trump’s birthday, but does not include MLK Day.

It’s symbolic. But symbols are not nothing. Symbols are how a state teaches people what counts as “patriotic,” who is welcomed into public space, and which freedoms are considered foundational.

And the symbolism sits alongside policy: early in the second Trump administration, the federal government moved to end or curtail DEI programs through executive action. In the Justice Department, reporting has described upheaval in the Civil Rights Division and a large departure of attorneys amid a shift in priorities.

So MLK Day 2026 isn’t just a day to remember. It’s a day to notice what is being asked of us—especially those of us who live at the intersections of diaspora, migration, faith, race, and empire.

King, Gandhi, and the discipline of nonviolence

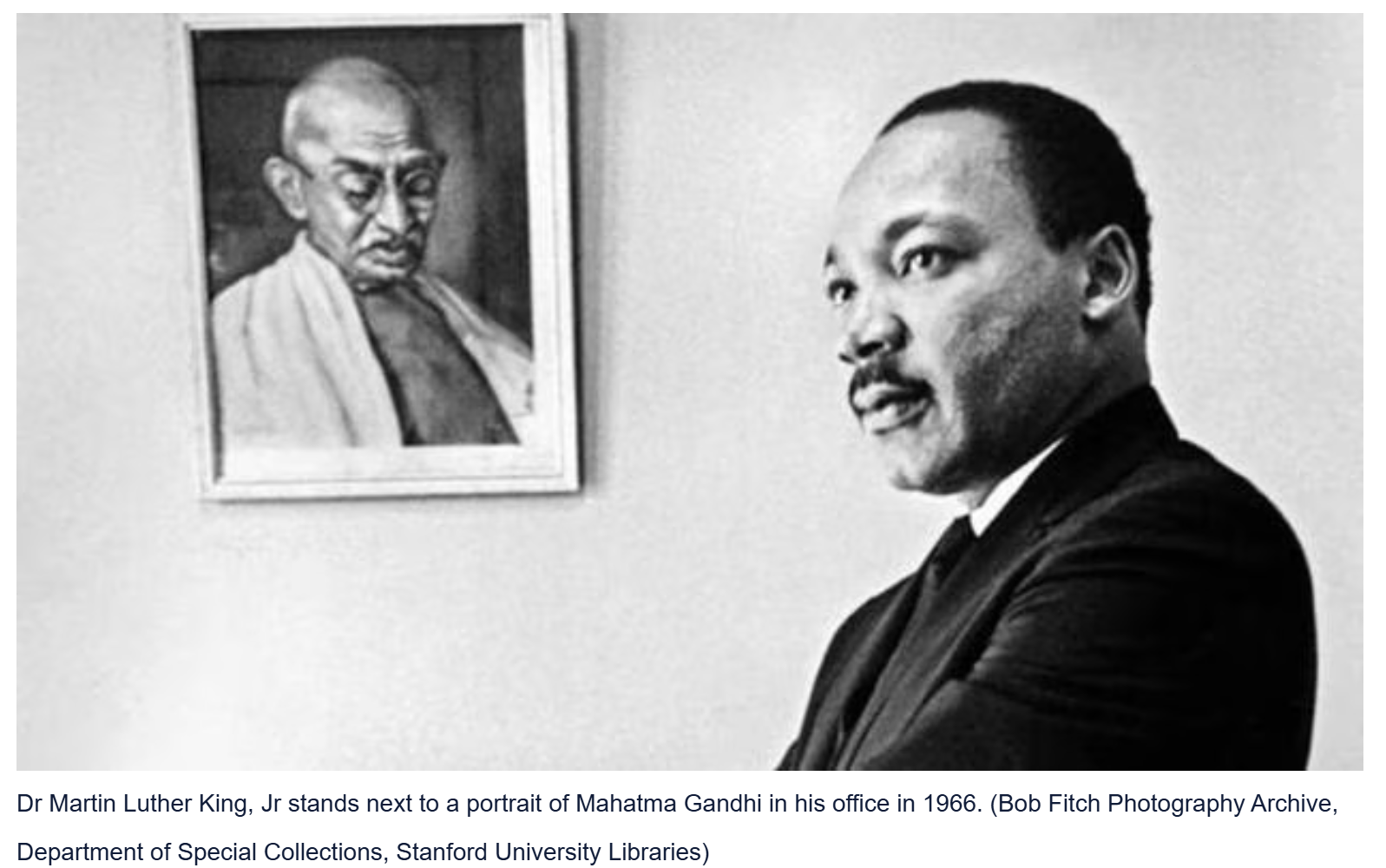

At the core of King’s public theology was a method as much as a message: nonviolent resistance as a moral discipline and a strategy for social transformation. King repeatedly credited Mahatma Gandhi as a guiding influence, calling him “the guiding light” of the technique of nonviolent social change.

King’s 1959 trip to India wasn’t a photo-op pilgrimage. It was a serious encounter with a philosophy: satyagraha as insistence on truth, and ahimsa as more than “peacefulness”—as a refusal to let brutality set the terms of politics.

For many South Asian Americans, this connection is not abstract. It is a living bridge between histories: the anti-colonial struggle that shaped our ancestral worlds, and the civil-rights struggle that shaped the country many of us now call home.

Civil rights changed the story of who could become “American”

It’s hard to say this plainly enough: the Civil Rights Movement didn’t only transform laws about segregation and voting. It helped transform the moral logic of the country—and that shift reshaped immigration.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 ended the older national-origins quota system that heavily favored Northern and Western Europe. The result was a profound change in who could immigrate, including increased immigration from Asia and South Asia over the decades that followed.

Many South Asian American families—directly or indirectly—are here because movements led by Black Americans forced the United States to confront itself.

If we say King’s name with gratitude, that gratitude has to be honest: not sentimental, not performative, not allergic to the hard parts of his legacy.

King’s vision was never only “civil rights.” It was human rights.

King’s message didn’t end at the edge of the United States. His Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech spoke to a struggle that was moral and global in scope, rooted in human dignity rather than a narrow nationalism.

And when King condemned the Vietnam War in 1967, he made clear that racism, militarism, and economic exploitation were intertwined.

This matters in 2026 because one of the most common ways to “honor” King is to keep him contained: a Southern story, a 1960s story, a story with a happy ending that requires nothing from us now.

But King’s work keeps spilling outward—toward questions of war and peace, labor and poverty, prisons and policing, migration and belonging.

Indo-Caribbean histories: where diasporas meet, under pressure

There is another bridge worth naming on MLK Day: Indo-Caribbean histories, forged through the brutal logic of colonial labor.

After the end of slavery, systems of indenture moved large numbers of Indians into places like Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, Suriname (and beyond), producing communities shaped by both the Indian diaspora and the African diaspora—sometimes in solidarity, sometimes in tension, always under the long shadow of empire. UNESCO’s documentation of indentured-labor records across sites including Guyana (1838–1917) and Trinidad and Tobago (1845–1917) gestures to the scale of this history.

For South Asian Americans, Indo-Caribbean communities make visible something the U.S. racial imagination often tries to erase: our stories are not separate from Black freedom struggles. We have been entangled—politically, culturally, economically—for a long time.

What it means to honor King in 2026

MLK Day is also a National Day of Service, a tradition strengthened in federal law in the 1990s—an effort to keep remembrance from becoming passive.

But service alone isn’t the point. King didn’t ask for charity. He asked for transformation.

So in a year when MLK Day is being flattened—when public institutions signal which histories matter and which can be quietly dropped—honoring King can look like:

Refusing the “sanitized King.” Reading and sharing the King who spoke about war, poverty, labor, and state violence—not only the King of a single famous speech.

Defending the infrastructure of rights. Paying attention to how civil-rights enforcement is being reshaped and what that means for communities targeted by discrimination.

Practicing nonviolence as clarity. Not as quietism, but as disciplined refusal to mirror the cruelty of the moment—paired with the courage to confront it.

Building cross-community solidarity that is specific. Naming caste and racism without letting either become a rhetorical costume. Not collapsing differences—learning them, honoring them, acting with them.

FAQ

Is MLK Day still a federal holiday in 2026?

Yes. Martin Luther King Jr. Day is still a U.S. federal holiday, observed on Monday, January 19, 2026.

What changed around MLK Day in 2026?

While the federal holiday remains, some public-facing policies have deemphasized it. One prominent example: the Department of the Interior’s 2026 list of National Park “fee-free days” does not include MLK Day and instead includes “Flag Day/President Trump’s birthday.”

How did Gandhi influence Martin Luther King Jr.?

King viewed Gandhi as a major influence on his method of nonviolent social change and traveled to India in 1959 to deepen his understanding of Gandhian principles.

How did the Civil Rights Movement affect South Asian immigration to the U.S.?

The broader civil-rights era helped create the political conditions for reforms like the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which ended the national-origins quota system that favored Northern and Western Europe and reshaped immigration patterns, including increased immigration from Asia over time.

Is MLK Day supposed to be a “day of service”?

Yes. MLK Day has long been framed as a National Day of Service, encouraging people to volunteer and participate in community action as part of honoring King’s legacy.

Why should South Asian Americans mark MLK Day with particular care?

Because King’s movement helped reshape the moral and legal landscape of the United States—including reforms that changed immigration—and because the King–Gandhi connection is a living bridge between anti-colonial struggle and civil-rights struggle.

Here are some online resources that provide valuable information on Martin Luther King Jr.'s connection to India and his legacy:

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute: This institute at Stanford University has a comprehensive section on King's India trip, detailing his experiences and the impact of this visit on his philosophy and strategies in the civil rights movement. Visit The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute for detailed accounts of his journey and meetings in India.

King Institute's Liberation Curriculum: Stanford University also offers lesson plans and educational materials about King's life, including his India trip. These resources are especially useful for educators and students. Visit the King Institute Liberation Curriculum for more information.

The Witness - Article on Asian Americans, MLK, and the Model Minority Myth: This article explores the relationship between Asian American communities and the civil rights movement, addressing how King's legacy impacts these communities. It can be accessed at The Witness.

University of Colorado Boulder's Resource on MLK's Legacy: This page provides insights into the full scope of King's activism and ideology, including resources for further reading and viewing.